The Zuiyo-maru carcass is a creature caught by the Japanese fishing trawler Zuiyō Maru off the coast of New Zealand in 1977.

The Zuiyo-maru carcass is a creature caught by the Japanese fishing trawler Zuiyō Maru off the coast of New Zealand in 1977.

The carcass’s peculiar appearance led to speculation that it might be the remains of a sea serpent or prehistoric plesiosaur.

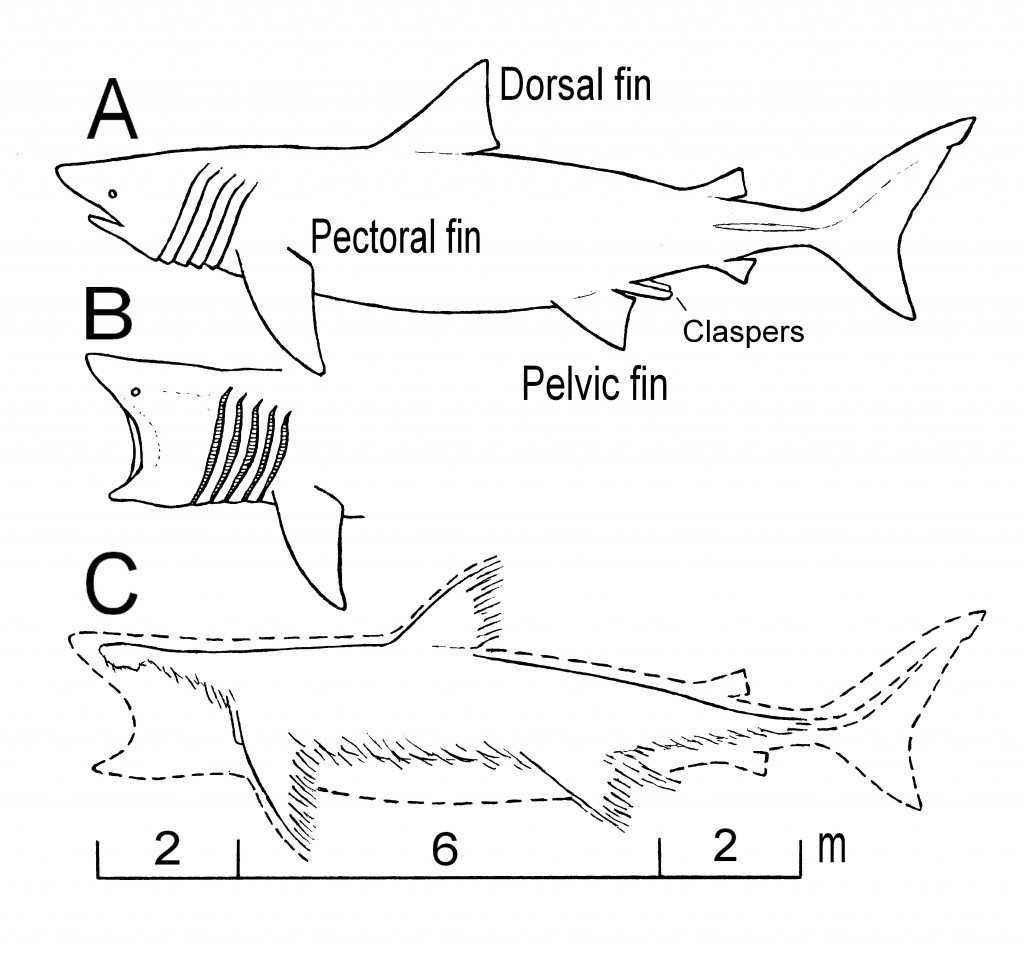

Although several scientists insisted it was “not a fish, whale, or any other mammal”, analysis later indicated it was most likely the carcass of a basking shark by comparing the number of sets of amino acids in the muscle tissue. Decomposing basking shark carcasses lose most of the lower head area and the dorsal and caudal fins first, making them resemble a plesiosaur.

Discovery

On April 25, 1977, the Japanese trawler Zuiyō Maru, sailing east of Christchurch, New Zealand, caught a strange, unknown creature in the trawl.

On April 25, 1977, the Japanese trawler Zuiyō Maru, sailing east of Christchurch, New Zealand, caught a strange, unknown creature in the trawl.

The crew was convinced it was an unidentified animal, but despite the potential biological significance of the curious discovery, the captain, Akira Tanaka, decided to dump the carcass into the ocean again so not to risk spoiling the caught fish. However, before that, some photos and sketches were taken of the creature, nicknamed “Nessie” by the crew, measurements were taken and some samples of skeleton, skin and fins were collected for further analysis by experts in Japan.

The discovery resulted in immense commotion and a “plesiosaur-craze” in Japan, and the shipping company ordered all its boats to try to relocate the dumped corpse, but with no apparent success.

Description

The foul-smelling, decomposing corpse reportedly weighed 1,800 kg and was about 10 m long.

According to the crew, the creature had a 1.5-m-long neck, four large, reddish fins, and a tail about 2.0 m long. It lacked a dorsal fin. No internal organs remained, but flesh and fat were somewhat intact.

Proposed explanations

Plesiosaur

Professor Tokio Shikama from Yokohama National University was convinced the remains were of a supposedly extinct plesiosaur. Dr. Fujiro Yasuda from Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology agreed with Shikama, “the photographs show the remains of a prehistoric animal”.

However, other scientists were more skeptical. According to Bengt Sjögren, Swedish paleontologist Hans-Christian Bjerring was soon interviewed by Swedish news agency Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå, and said:

“If it’s true that the Japanese collected samples of fins and skin, it would be possible to conclude from a microscope what it is. If it would be shown to be a hitherto unknown animal from the sea, it is as big of a sensation as the discovery of the coelacanth in 1938… but there is reason to be suspicious of the claims of plesiosaurs, for example, as the marine environment and fauna changed drastically since the age of the plesiosaurs on earth.”

Another Swedish scientist, Ove Persson, was also critical of the plesiosaur interpretation.

He recalled other discoveries of similar dead marine creatures resembling plesiosaurs that on closer inspection revealed them to be just decomposed, unusually large sharks. He also added,

“The discovery of the coelacanth was not as strange as if a plesiosaur would be discovered. The plesiosaur is much bigger and breathes with lungs. It seems incredible that it would manage to remain hidden.”

Basking shark

A team of Japanese scientists, Tadayoshi Sasaki and Shigeru Kimura from the Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, Ikuo Obata from the National Museum of Nature and Science, and Toshio Ikuya from the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute at the University of Tokyo, jointly concluded, while the identity of the carcass could not be determined with certainty, the carcass was most likely that of a large shark.

On July 28, 1977, the Zuiyō Maru carcass was commented upon in the international science magazine New Scientist. A scientist from the Natural History Museum in London had the same opinion as Bjerring and Persson, that the remains were not from a plesiosaur.

The decomposition pattern of a basking shark, whose spine and brain case is relatively highly calcified for a cartilaginous fish, can be expected to produce a similar shape to a plesiosaur; the first parts that fall off during decomposition are the lower jaw, the gill area, and the dorsal and caudal fins. Of the view that the carcass was explained as a pleiosaur, Sjögren concluded, “it was the infamous old ‘Stronsay Beast’ that once again haunted like on innumerable other occasions. The scholars in Japan went into the same easy trap as the Scottish naturalists did in the 19th century.”