The thylacine ( THY-lə-seen, or Thylacinus cynocephalus, Greek for “dog-headed pouched one”) was the largest known carnivorous marsupial of modern times. It is commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger (because of its striped back) or the Tasmanian wolf. Native to continental Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea, it is thought to have become extinct in the 20th century. It was the last extant member of its family, Thylacinidae; specimens of other members of the family have been found in the fossil record dating back to the early Miocene.

The thylacine had become extremely rare or extinct on the Australian mainland before British settlement of the continent, but it survived on the island of Tasmania along with several other endemic species, including the Tasmanian devil. Intensive hunting encouraged by bounties is generally blamed for its extinction, but other contributing factors may have been disease, the introduction of dogs, and human encroachment into its habitat. Despite its official classification as extinct, sightings are still reported, though none have been conclusively proven.

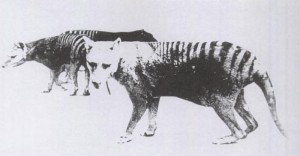

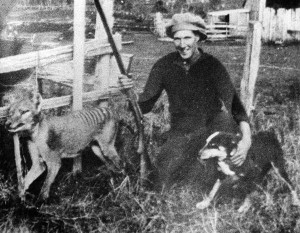

Surviving evidence suggests that it was a relatively shy, nocturnal creature with the general appearance of a medium-to-large-size dog, except for its stiff tail and abdominal pouch (which was reminiscent of a kangaroo) and a series of dark transverse stripes that radiated from the top of its back (making it look a bit like a tiger).

Like the tigers and wolves of the Northern Hemisphere, from which it obtained two of its common names, the thylacine was an apex predator. As a marsupial, it was not closely related to these placental mammals, but because of convergent evolution it displayed the same general form and adaptations. Its closest living relative is thought to be either the Tasmanian devil or numbat. The thylacine was one of only two marsupials to have a pouch in both sexes (the other being the water opossum). The male thylacine had a pouch that acted as a protective sheath, covering his external reproductive organs while he ran through thick brush. It has been described as a formidable predator because of its ability to survive and hunt prey in extremely sparsely populated areas.

The thylacine is a strong candidate for cloning and other molecular science projects due to its recent demise and the existence of several well preserved specimens.

Evolution

The modern thylacine first appeared about 4 million years ago. Species of the family Thylacinidae date back to the beginning of the Miocene; since the early 1990s, at least seven fossil species have been uncovered at Riversleigh, part of Lawn Hill National Park in northwest Queensland. Dickson’s thylacine (Nimbacinus dicksoni) is the oldest of the seven discovered fossil species, dating back to 23 million years ago. This thylacinid was much smaller than its more recent relatives.

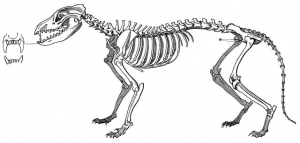

The largest species, the powerful thylacine (Thylacinus potens) which grew to the size of a wolf, was the only species to survive into the late Miocene. In late Pleistocene and early Holocene times, the modern thylacine was widespread (although never numerous) throughout Australia and New Guinea.An example of convergent evolution, the thylacine showed many similarities to the members of the dog family, Canidae, of the Northern Hemisphere: sharp teeth, powerful jaws, raised heels and the same general body form. Since the thylacine filled the same ecological niche in Australia as the dog family did elsewhere, it developed many of the same features. Despite this, it is unrelated to any of the Northern Hemisphere predators.

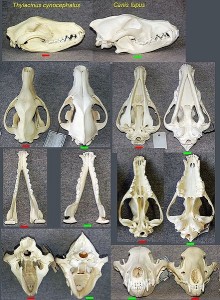

They are easy to tell from a true dog because of the stripes on the back but the skeleton is harder to distinguish. Zoology students at Oxford had to identify 100 zoological specimens as part of the final exam. Word soon got around that, if ever a ‘dog’ skull was given, it was safe to identify it as Thylacinus on the grounds that anything as obvious as a dog skull had to be a catch. Then one year the examiners, to their credit, double bluffed and put in a real dog skull. The easiest way to tell the difference is by the two prominent holes in the palate bone, which are characteristic of marsupials generally. — Richard Dawkins, The Ancestor’s Tale

Discovery and taxonomy

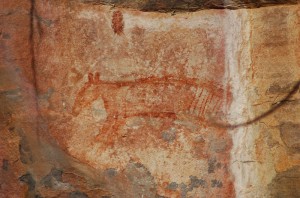

Petroglyph images of the thylacine can be found at the Dampier Rock Art Precinct on the Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia. By the time the first European explorers arrived, the animal was already extinct in mainland Australia and rare in Tasmania. Europeans may have encountered it as far back as 1642 when Abel Tasman first arrived in Tasmania. His shore party reported seeing the footprints of “wild beasts having claws like a Tyger”. Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, arriving with the Mascarin in 1772, reported seeing a “tiger cat”. Positive identification of the thylacine as the animal encountered cannot be made from this report since the tiger quoll (Dasyurus maculatus) is similarly described. The first definitive encounter was by French explorers on 13 May 1792, as noted by the naturalist Jacques Labillardière, in his journal from the expedition led by D’Entrecasteaux. However, it was not until 1805 that William Paterson, the Lieutenant Governor of Tasmania, sent a detailed description for publication in the Sydney Gazette.

The first detailed scientific description was made by Tasmania’s Deputy Surveyor-General, George Harris in 1808, five years after first settlement of the island. Harris originally placed the thylacine in the genus Didelphis, which had been created by Linnaeus for the American opossums, describing it as Didelphis cynocephala, the “dog-headed opossum”. Recognition that the Australian marsupials were fundamentally different from the known mammal genera led to the establishment of the modern classification scheme, and in 1796, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire created the genus Dasyurus where he placed the thylacine in 1810. To resolve the mixture of Greek and Latin nomenclature, the species name was altered to cynocephalus. In 1824, it was separated out into its own genus, Thylacinus, by Temminck. The common name derives directly from the genus name, originally from the Greek θύλακος (thýlakos), meaning “pouch” or “sack”.

Several studies support the thylacine as being a basal member of the Dasyuromorphia and the Tasmanian devil as its closest living relative. However, research published in Genome Research in January 2009 suggests the numbat may be more basal than the devil and more closely related to the thylacine.

Description

Descriptions of the thylacine vary, as evidence is restricted to preserved joey specimens, fossil records, skins and skeletal remains, black and white photographs and film of the animal in captivity, and accounts from the field.

Thylacine held the title of Australia’s largest predator until about 3500 years ago. The thylacine resembled a large, short-haired dog with a stiff tail which smoothly extended from the body in a way similar to that of a kangaroo. Many European settlers drew direct comparisons with the hyena, because of its unusual stance and general demeanour. Its yellow-brown coat featured 13 to 21 distinctive dark stripes across its back, rump and the base of its tail, which earned the animal the nickname “tiger”. The stripes were more pronounced in younger specimens, fading as the animal got older. One of the stripes extended down the outside of the rear thigh. Its body hair was dense and soft, up to 15 mm (0.6 in) in length; in juveniles the tip of the tail had a crest. Its rounded, erect ears were about 8 cm (3.1 in) long and covered with short fur. Colouration varied from light fawn to a dark brown; the belly was cream-coloured.

The mature thylacine ranged from 100 to 130 cm (39 to 51 in) long, plus a tail of around 50 to 65 cm (20 to 26 in). The largest measured specimen was 290 cm (9.5 ft) from nose to tail. Adults stood about 60 cm (24 in) at the shoulder and weighed 20 to 30 kg (40 to 70 lb). There was slight sexual dimorphism with the males being larger than females on average.

All known Australian footage of live thylacines, shot in Hobart Zoo, Tasmania, in 1911, 1928, and 1933. Two other films are known, shot in London Zoo The female thylacine had a pouch with four teats, but unlike many other marsupials, the pouch opened to the rear of its body. Males had a scrotal pouch, unique amongst the Australian marsupials, into which they could withdraw their scrotal sac.

The thylacine was able to open its jaws to an unusual extent: up to 120 degrees. This capability can be seen in part in David Fleay’s short black-and-white film sequence of a captive thylacine from 1933. The jaws were muscular but weak and had 46 teeth.

Thylacine footprints could be distinguished from other native or introduced animals; unlike foxes, cats, dogs, wombats or Tasmanian devils, thylacines had a very large rear pad and four obvious front pads, arranged in almost a straight line. The hindfeet were similar to the forefeet but had four digits rather than five. Their claws were non-retractable.

The early scientific studies suggested it possessed an acute sense of smell which enabled it to track prey, but analysis of its brain structure revealed that its olfactory bulbs were not well developed. It is likely to have relied on sight and sound when hunting instead. Some observers described it having a strong and distinctive smell, others described a faint, clean, animal odour, and some no odour at all. It is possible that the thylacine, like its relative, the Tasmanian devil, gave off an odour when agitated.

The thylacine was noted as having a stiff and somewhat awkward gait, making it unable to run at high speed. It could also perform a bipedal hop, in a fashion similar to a kangaroo—demonstrated at various times by captive specimens. Guiler speculates that this was used as an accelerated form of motion when the animal became alarmed. The animal was also able to balance on its hind legs and stand upright for brief periods.

Observers of the animal in the wild and in captivity noted that it would growl and hiss when agitated, often accompanied by a threat-yawn. During hunting it would emit a series of rapidly repeated guttural cough-like barks (described as “yip-yap”, “cay-yip” or “hop-hop-hop”), probably for communication between the family pack members. It also had a long whining cry, probably for identification at distance, and a low snuffling noise used for communication between family members.

Ecology and behaviour

Little is known about the behaviour or habitat of the thylacine. A few observations were made of the animal in captivity, but only limited, anecdotal evidence exists of the animal’s behaviour in the wild. Most observations were made during the day whereas the thylacine was naturally nocturnal. Those observations, made in the twentieth century, may have been atypical as they were of a species already under the stresses that would soon lead to its extinction. Some behavioural characteristics have been extrapolated from the behaviour of its close relative, the Tasmanian devil.

The thylacine probably preferred the dry eucalyptus forests, wetlands, and grasslands in continental Australia. Indigenous Australian rock paintings indicate that the thylacine lived throughout mainland Australia and New Guinea. Proof of the animal’s existence in mainland Australia came from a desiccated carcass that was discovered in a cave in the Nullarbor Plain in Western Australia in 1990; carbon dating revealed it to be around 3,300 years old.

In Tasmania it preferred the woodlands of the midlands and coastal heath, which eventually became the primary focus of British settlers seeking grazing land for their livestock. The striped pattern may have provided camouflage in woodland conditions, but it may have also served for identification purposes. The animal had a typical home range of between 40 and 80 km2 (15 and 31 sq mi). It appears to have kept to its home range without being territorial; groups too large to be a family unit were sometimes observed together.

The thylacine was a nocturnal and crepuscular hunter, spending the daylight hours in small caves or hollow tree trunks in a nest of twigs, bark or fern fronds. It tended to retreat to the hills and forest for shelter during the day and hunted in the open heath at night. Early observers noted that the animal was typically shy and secretive, with awareness of the presence of humans and generally avoiding contact, though it occasionally showed inquisitive traits. At the time, much stigma existed in regard to its “fierce” nature, however this is likely to be due to its perceived threat to agriculture.

There is evidence for at least some year-round breeding (cull records show joeys discovered in the pouch at all times of the year), although the peak breeding season was in winter and spring. They would produce up to four cubs per litter (typically two or three), carrying the young in a pouch for up to three months and protecting them until they were at least half adult size. Early pouch young were hairless and blind, but they had their eyes open and were fully furred by the time they left the pouch. After leaving the pouch, and until they were developed enough to assist, the juveniles would remain in the lair while their mother hunted. Thylacines only once bred successfully in captivity, in Melbourne Zoo in 1899. Their life expectancy in the wild is estimated to have been 5 to 7 years, although captive specimens survived up to 9 years.

Diet

Although there are methods that can be used to identify the diet and feeding behavior of thylacine, findings and theories on this subject remain hotly debated. A study published in 2011 yields some insight: “Dental and biogeochemical evidence suggests that T. cynocephalus was a hypercarnivore restricted to eating vertebrate flesh” The thylacine was exclusively carnivorous. Its stomach was muscular with an ability to distend to allow the animal to eat large amounts of food at one time, probably an adaptation to compensate for long periods when hunting was unsuccessful and food scarce. Analysis of the skeletal frame and observations of it in captivity suggest that it preferred to single out a target animal and pursue that animal until it was exhausted. Some studies conclude that the animal may have hunted in small family groups, with the main group herding prey in the general direction of an individual waiting in ambush. Trappers reported it as an ambush predator.

Little is known of the thylacine’s diet and feeding behaviour. Prey is believed to have included kangaroos, wallabies and wombats, birds and small animals such as potoroos and possums. One prey animal may have been the once common Tasmanian Emu. The emu was a large, flightless bird which shared the habitat of the thylacine and was hunted to extinction around 1850, possibly coinciding with the decline in thylacine numbers. Both dingoes and foxes have been noted to hunt the emu on the mainland. European settlers believed the thylacine to prey upon farmers’ sheep and poultry. Throughout the twentieth century, the thylacine was often characterised as primarily a blood drinker; according to Robert Paddle, the story’s popularity seems to have originated from a single second-hand account heard by Geoffrey Smith in a shepherd’s hut. In captivity, thylacines were fed a wide variety of foods, including dead rabbits and wallabies as well as beef, mutton, horse, and occasionally poultry. Tasmania’s leading naturalist Michael Sharland published an article in 1957 stating that a captive thylacine refused to eat either dead wallaby flesh or to kill and eat a live wallaby offered to it, but “ultimately it was persuaded to eat by having the smell of blood from a freshly killed wallaby put before its nose.”

A 2011 study by the University of New South Wales using advanced computer modelling indicated that the thylacine had surprisingly feeble jaws. Animals usually take prey close to their own body size, but an adult thylacine of around 30 kilograms (66 lb) was found to be incapable of handling prey much larger than 5 kilograms (11 lb). Researchers believe thylacines only ate small animals such as bandicoots and possums, putting them into direct competition with the Tasmanian devil and the Tiger Quoll. Such specialisation probably made the thylacine susceptible to small disturbances to the ecosystem.

Although the living grey wolf is widely seen as thylacine’s counterpart, a recent study proposes that thylacine was more of an ambush predator as opposed to a pursuit predator. In fact, the predatory behaviour of the thylacine was probably closer to that of ambushing felids than to that of large pursuit canids. Consequently, at least in terms of the postcranial anatomy, the vernacular name of ‘Tasmanian tiger’ may be more apt than that of ‘marsupial wolf’

Extinction

Extinction from mainland Australia

The thylacine is likely to have become near-extinct in mainland Australia about 2,000 years ago, and possibly earlier in New Guinea. The absolute extinction is attributed to competition from indigenous humans and invasive dingoes. However, doubts exist over the impact of the dingo since the two species would not have been in direct competition with one another as the dingo hunts primarily during the day, whereas it is thought that the thylacine hunted mostly at night. In addition, the thylacine had a more powerful build, which would have given it an advantage in one-on-one encounters. Recent morphological examinations of dingo and thylacine skulls show that although the dingo had a weaker bite, its skull could resist greater stresses, allowing it to pull down larger prey than the thylacine could. The thylacine was also much less versatile in diet than the omnivorous dingo. Their environments clearly overlapped: thylacine subfossil remains have been discovered in proximity to those of dingoes. The adoption of the dingo as a hunting companion by the indigenous peoples would have put the thylacine under increased pressure.

Prideaux et al. (2010) examined the issue of extinction in the late Quaternary period in southwestern Australia. This paper notes that Australia lost 90% or more of its larger terrestrial vertebrates during this time, with the notable exceptions of the kangaroo and the thylacine. The results show that the humans were obviously one of the major factors in the extinction of many species in Australia. But in reality, it was not until the humans had an adverse effect on the environment and brought disease to Australia that their arrival drove the Thylacine to extinction.

Menzies et al. (2012) examined the relationship of the genetic diversity of the thylacines before their extinction. The results of their investigation indicated that the last of the thylacines in Australia, on top of the threats from dingoes, had limited genetic diversity, due to their complete geographic isolation from mainland Australia.

Johnson and Wroe (2003) observed the relationship between the dingo and the extinctions of the Tasmanian devil, the Thylacine, and the Tasmanian native hen and the arrival of humans. The paper observed the obviously competitive relationship between the dingo and the thylacine and the Tasmanian devil, and noted that the dingo may have actually fed on the native hen. Yet, the paper concludes, people ignore the emergence of humans on the continent among all of this. In the end, the competitiveness of the dingo and Thylacine populations led to the extinctions of the Thylacine but the arrival of the humans only further exacerbated this.

Another study brings disease into the debate as a major factor in thylacine’s extinction: “Casually collected anecdotal records and early boutity analyses have, at times, prompted the suggestion that disease was a major factor in the extinction of the species, that occurred when the last known specimen died in Hobart Zoo during the night of 7th September, 1936.” This study also suggests that were it not for an epidemiological influence, the extinction of thylacine would have been at best prevented, at worst postponed. “the chance of saving the species, through changing public opinion, and the re-establishment of captive breeding, could have heen possible. But the marsupi-carnivore disease, with its dramatic effect on individual thylacine longevity and juvenile mortality, came far too soon, and spread far too quickly.”

Rock paintings from the Kakadu National Park clearly show that thylacines were hunted by early humans.

Extinction in Tasmania

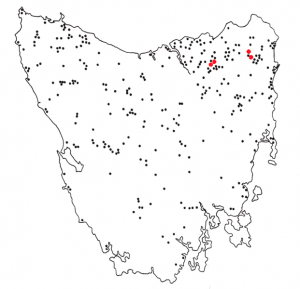

Although the thylacine had been close to extinction on mainland Australia by the time of European settlement, and went extinct there some time in the nineteenth century, it survived into the 1930s on the island state of Tasmania. At the time of the first settlement, the heaviest distributions were in the northeast, northwest and north-midland regions of the state. They were rarely sighted during this time but slowly began to be credited with numerous attacks on sheep. This led to the establishment of bounty schemes in an attempt to control their numbers. The Van Diemen’s Land Company introduced bounties on the thylacine from as early as 1830, and between 1888 and 1909 the Tasmanian government paid £1 per head for dead adult thylacines and ten shillings for pups. In all they paid out 2,184 bounties, but it is thought that many more thylacines were killed than were claimed for. Its extinction is popularly attributed to these relentless efforts by farmers and bounty hunters. However, it is likely that multiple factors led to its decline and eventual extinction, including competition with wild dogs introduced by European settlers, erosion of its habitat, the concurrent extinction of prey species, and a distemper-like disease that also affected many captive specimens at the time. Whatever the reason, the animal had become extremely rare in the wild by the late 1920s. Despite the fact that the thylacine was believed by many to be responsible for attacks on the sheep, in 1928 the Tasmanian Advisory Committee for Native Fauna had recommended a reserve to protect any remaining thylacines, with potential sites of suitable habitat including the Arthur-Pieman area of western Tasmania.

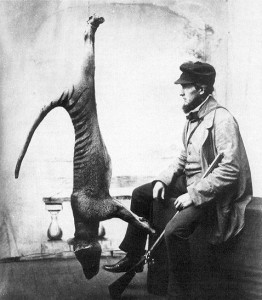

The last known Thylacine to be killed in the wild was shot in 1930 by Wilf Batty, a farmer from Mawbanna, in the northeast of the state. The animal, believed to have been a male, had been seen around Batty’s house for several weeks.

“Benjamin” and searches

The last captive thylacine, later referred to as “Benjamin” (although its sex has never been confirmed) was captured in 1933 by Elias Churchill and sent to the Hobart Zoo where it lived for three years. Frank Darby, who claimed to have been a keeper at Hobart Zoo, suggested “Benjamin” as having been the animal’s pet name in a newspaper article of May 1968. However, no documentation exists to suggest that it ever had a pet name, and Alison Reid (de facto curator at the zoo) and Michael Sharland (publicist for the zoo) denied that Frank Darby had ever worked at the zoo or that the name “Benjamin” was ever used for the animal. Darby also appears to be the source for the claim that the last thylacine was a male; photographic evidence suggests it was female. This thylacine died on 7 September 1936. It is believed to have died as the result of neglect—locked out of its sheltered sleeping quarters, it was exposed to a rare occurrence of extreme Tasmanian weather: extreme heat during the day and freezing temperatures at night. This thylacine features in the last known motion picture footage of a living specimen: 62 seconds of black-and-white footage showing it pacing backwards and forwards in its enclosure in a clip taken in 1933 by naturalist David Fleay. National Threatened Species Day has been held annually since 1996 on 7 September in Australia, to commemorate the death of the last officially recorded thylacine.

Although there had been a conservation movement pressing for the thylacine’s protection since 1901, driven in part by the increasing difficulty in obtaining specimens for overseas collections, political difficulties prevented any form of protection coming into force until 1936. Official protection of the species by the Tasmanian government was introduced on 10 July 1936, 59 days before the last known specimen died in captivity.

The results of subsequent searches indicated a strong possibility of the survival of the species in Tasmania into the 1960s. Searches by Dr. Eric Guiler and David Fleay in the northwest of Tasmania found footprints and scats that may have belonged to the animal, heard vocalisations matching the description of those of the thylacine, and collected anecdotal evidence from people reported to have sighted the animal. Despite the searches, no conclusive evidence was found to point to its continued existence in the wild. Between 1967 and 1973 zoologist Jeremy Griffith and dairy farmer James Malley conducted what is regarded as the most intensive search ever carried out, including exhaustive surveys along Tasmania’s west coast; installation of automatic camera stations; prompt investigations of claimed sightings; and in 1972 the creation of the Thylacine Expeditionary Research Team with Dr Bob Brown, which concluded without finding any evidence of the thylacine’s existence.

A number of ongoing search efforts are currently being undertaken; typically these are self-funded initiatives conducted by thylacine enthusiasts who vary in approach, background knowledge and general modus operandi. Some searchers are ‘believers’, conducting searches on the basis that they firmly believe the thylacine to be yet alive. Other groups have a more practical and pragmatic view, hoping the thylacine to be extant although understanding the probabilities of its being extinct. The two different view points are important when understanding how each group views potential evidence or proof: the ‘believers’ group tend to err on the side of interpreting evidence with bias toward the thylacine being extant, while the skeptics will look for more plausible explanations regarding any evidence presented. One such group that is relatively active in producing videos for debate and analysis is the Thylacine Research Unit.

The thylacine held the status of endangered species until the 1980s. International standards at the time stated that an animal could not be declared extinct until 50 years had passed without a confirmed record. Since no definitive proof of the thylacine’s existence in the wild had been obtained for more than 50 years, it met that official criterion and was declared extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature in 1982 and by the Tasmanian government in 1986. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is more cautious, listing it as “possibly extinct”.

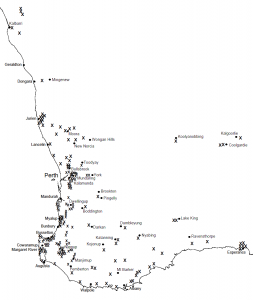

Unconfirmed sightings

The Australian Rare Fauna Research Association reports having 3,800 sightings on file from mainland Australia since the 1936 extinction date, while the Mystery Animal Research Centre of Australia recorded 138 up to 1998, and the Department of Conservation and Land Management recorded 65 in Western Australia over the same period. Independent thylacine researchers Buck and Joan Emburg of Tasmania report 360 Tasmanian and 269 mainland post-extinction 20th-century sightings, figures compiled from a number of sources. On the mainland, sightings are most frequently reported in Southern Victoria.

Some sightings have generated a large amount of publicity. In 1973, Gary and Liz Doyle shot ten seconds of 8mm film showing an unidentified animal running across a South Australian road. Attempts to positively identify the creature as a thylacine have been impossible due to the poor quality of the film. In 1982 a researcher with the Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service, Hans Naarding, observed what he believed to be a thylacine for three minutes during the night at a site near Arthur River in northwestern Tasmania. The sighting led to an extensive year-long government-funded search. In 1985, Aboriginal tracker Kevin Cameron produced five photographs which appear to show a digging thylacine, which he stated he took in western Australia. In January 1995, a Parks and Wildlife officer reported observing a thylacine in the Pyengana region of northeastern Tasmania in the early hours of the morning. Later searches revealed no trace of the animal. In 1997, it was reported that locals and missionaries near Mount Carstensz in Western New Guinea had sighted thylacines. The locals had apparently known about them for many years but had not made an official report. In February 2005 Klaus Emmerichs, a German tourist, claimed to have taken digital photographs of a thylacine he saw near the Lake St Clair National Park, but the authenticity of the photographs has not been established. The photos were published in April 2006, fourteen months after the sighting. The photographs, which showed only the back of the animal, were said by those who studied them to be inconclusive as evidence of the thylacine’s continued existence. Due to the uncertainty of whether the species is still extant or not, the thylacine is sometimes regarded as a cryptid.

Rewards

In 1983, the American media mogul Ted Turner offered a $100,000 reward for proof of the continued existence of the thylacine.

A letter sent in response to an inquiry by a thylacine-searcher, Murray McAllister, in 2000 indicated that the reward had been withdrawn. In March 2005, Australian news magazine The Bulletin, as part of its 125th anniversary celebrations, offered a $1.25 million reward for the safe capture of a live thylacine. When the offer closed at the end of June 2005 no one had produced any evidence of the animal’s existence. An offer of $1.75 million has subsequently been offered by a Tasmanian tour operator, Stewart Malcolm. Trapping is illegal under the terms of the thylacine’s protection, so any reward made for its capture is invalid, since a trapping licence would not be issued.

A $250,000 reward for any form of evidence that the thylacine still exists today was offered by tourist entrepreneur Peter Wright. Other rewards were also put out by the World Wide Fund for Nature. This created a spur of researchers and scientists and laymen to look for any kind of evidence of a thylacine alive today.

Modern research and projects

Records of all specimens, many of which are in European collections, are now held in the International Thylacine Specimen Database.

The Australian Museum in Sydney began a cloning project in 1999. The goal was to use genetic material from specimens taken and preserved in the early 20th century to clone new individuals and restore the species from extinction. Several microbiologists have dismissed the project as a public relations stunt and its chief proponent, Professor Mike Archer, received a 2002 nomination for the Australian Skeptics Bent Spoon Award for “the perpetrator of the most preposterous piece of paranormal or pseudo-scientific piffle.”

In late 2002 the researchers had some success as they were able to extract replicable DNA from the specimens. On 15 February 2005, the museum announced that it was stopping the project after tests showed the DNA retrieved from the specimens had been too badly degraded to be usable. In May 2005, Professor Michael Archer, the University of New South Wales Dean of Science at the time, former director of the Australian Museum and evolutionary biologist, announced that the project was being restarted by a group of interested universities and a research institute.

The International Thylacine Specimen Database was completed in April 2005 and is the culmination of a four-year research project to catalog and digitally photograph, if possible, all known surviving thylacine specimen material held within museum, university and private collections. The master records are held by the Zoological Society of London.

In 2008 researchers Andrew J. Pask and Marilyn B. Renfree from the University of Melbourne and Richard R. Behringer from the University of Texas reported that they managed to restore functionality of a gene Col2A1 enhancer obtained from 100 year-old ethanol-fixed thylacine tissues from museum collections. The genetic material was found working in transgenic mice. The research enhanced hopes of eventually restoring the population of thylacines. That same year, another group of researchers successfully sequenced the complete thylacine mitochondrial genome from two museum specimens. Their success suggests that it may be feasible to sequence the complete thylacine nuclear genome from museum specimens. Their results were published in the journal Genome Research in 2009.

Stewart Brand spoke at TED2013 about the ethics and possibilities of de-extinction, and made reference to thylacine in his talk.

Cultural references

The best known illustrations of Thylacinus cynocephalus were those in Gould’s The Mammals of Australia (1845–63), often copied since its publication and the most frequently reproduced, and given further exposure by Cascade Brewery’s appropriation for its label in 1987. The government of Tasmania published a monochromatic reproduction of the same image in 1934, the author Louisa Anne Meredith also copied it for Tasmanian Friends and Foes (1881).

The thylacine has been used extensively as a symbol of Tasmania. The animal is featured on the official Tasmanian coat of arms. It is used in the official logos of Tourism Tasmania and City of Launceston. It is also used on the University of Tasmania’s ceremonial mace and the badge of the submarine HMAS Dechaineux. Since 1998, it has been prominently displayed on Tasmanian vehicle number plates.

The plight of the thylacine was featured in a campaign for The Wilderness Society entitled We used to hunt thylacines. In video games, boomerang-wielding Ty the Tasmanian Tiger is the star of his own trilogy. Characters in the early 1990s cartoon Taz-Mania included the neurotic Wendell T. Wolf, the last surviving Tasmanian wolf. Tiger Tale is a children’s book based on an Aboriginal myth about how the thylacine got its stripes. The thylacine character Rolf is featured in the extinction musical Rockford’s Rock Opera. The thylacine is the mascot for the Tasmanian cricket team, and has appeared in postage stamps from Australia, Equatorial Guinea, and Micronesia. The Djin-Jum Man (1998, Clarion Books) a story by children’s author Al Carusone features a hunter pursued by a powerful curse for killing the last of the Tasmanian Tigers.

The thylacine and its extinction are prominently featured in Howling III: The Marsupials, a 1987 Australian comedy horror sequel to The Howling. In the film, werewolves in Australia are discovered to have evolved from the thylacine rather than any subspecies of Canis lupus, differentiating them from other, more traditional werewolves in the film. The human/thylacine hybrids, being (at least partially) marsupials, have pouches in which their young mature after birth. The film draws parallels between the hunting and extinction of thylacines and the struggle of the Australian werewolves to survive as they are hunted by humans who believe they are dangerous. The 1933 footage of “Benjamin” makes an appearance in the film.

The Hunter is a novel by Julia Leigh about an Australian hunter who sets out to find the last thylacine. The novel has been adapted into a 2011 film by the same name directed by Daniel Nettheim, and starring Willem Dafoe.

In 2012, a demonic thylacine shapeshifter was introduced as the main antagonist in the #DeadThings series by author Reese Riley.

Hi Mark,

I believe I have seen a puppy of a Thylacine.

My husband and I walked up Mount Taranaki to watch the sunrise.

As I was walking up the track, It was still dark so I made sure to stay close to the railing which had dense bush on the other side of it so I would hold the railing in between Bush hanging over it.

I was wearing a headlamp as well. So when I spotted a clear spot coming up on the railing I went to place my hand on it and that’s when I saw a baby Thylacine crawling under the bush along the railing. Right where I was to put my hand that’s where it was, my head lamp was good so I got a really good look at it.

We both actually froze mid step and stared at each other for a few seconds. What I saw I could only describe at first as a Ring tailed Lima crossed with a fox.

It had big yellow eyes, small round teddy bear shaped ears, and it was smiling at me like a lizard type smile.

It’s fur looked soft and fluffy almost like possum fur or mink and it had distinctive dark brown stripes down its back to its tail the colour in between was a chocolate/caramel brown.

It was about the size of a large cat and upon seeing me it went into a submissive dog position on its stomach looking directly at me with its weirdly wide smile and big eyes.

It was so strange looking that once I realized it wasn’t moving I got scared and quickly waved my arm at it to scare it off as I quickly carried on up the track.

I have videos of when we went on the track but not of the animal I’m sorry. I can show you where exactly I saw it on the map and date and time we were there.

Feel free to contact me should you want further information, I feel so relieved to have found the exact picture of the animal I saw that morning.

Cheers

Tori

Hi, thanks for posting this. I’m very intrigued! Can’t think of any other animal in this country that fits that description. So good that you got a good look at it before it disappeared. I don’t get that way very often, but I’m keen to know the general area if you have it on a map. I’ll see if I can find people in the area that might like to get involved in a search. Thanks, Mark