Moa were large, flightless birds that lived in New Zealand until about 500 years ago.

Moa were large, flightless birds that lived in New Zealand until about 500 years ago.

There were 10 species of these extinct birds. They belong to the ratite group of birds, in the order Dinornithiformes, which also includes ostriches, emus and kiwi.

Moa were hunted to extinction by Māori, who found them easy targets. Their flesh was eaten, their feathers and skins were made into clothing. The bones were used for fish hooks and pendants.

The two largest species, Dinornis robustus and Dinornis novaezelandiae, reached about 3.6 m (12 ft) in height with neck outstretched, and weighed about 230 kg (510 lb).

They were the dominant herbivores in New Zealand’s forest, shrubland and subalpine ecosystems for thousands of years, and until the arrival of the Maori were hunted only by the Haast’s Eagle. It is generally considered that most, if not all, species of moa died out by A.D. 1400 due to overhunting by the Māori and habitat decline.

Scientific classification

Ratite birds

They are classed as a member of the ratite group of birds, which includes the rheas (South America), ostriches (Africa and Europe–Asia), elephant birds (Madagascar), emus and cassowaries (Australia and Papua New Guinea) and kiwi (New Zealand). Ratites (from ratis, Latin for raft) are so named because their sternum (breastbone) is ‘raft-like’, or without a ‘keel’. Ratites are included in the larger group Palaeognathae (literally ‘old mouth’, due to the distinctive shape of their jaw). Palaeognaths are the sister group to all other birds, which are called neognaths.

Nearest relatives

Ever since moa were revealed to European scientists in 1840, the question of the bird’s closest relative has been debated. Many people assumed that it was the kiwi because the birds lived in the same area. Some researchers still believe this. However, kiwi have wings and moa did not. Others argue that moa are more closely related to emus and cassowaries.

Certainly, moa are distantly related to the other ratites and have had an independent lineage for millennia. The moa ancestor was probably on the land that became New Zealand when it separated from the supercontinent Gondwana, some 85 million years ago. Moa evolved to become unlike any other bird, so comparisons are difficult. They differ genetically from other ratites.

Description

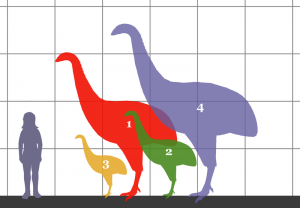

Size comparison between 4 moa species and a human.

1. Dinornis novaezealandiae

2. Emeus crassus

3. Anomalopteryx didiformis

4. Dinornis robustus

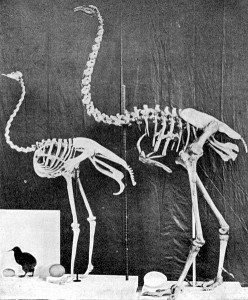

Although moa were traditionally reconstructed in an upright position to create impressive height, analysis of their vertebral articulation indicates that they probably carried their heads forward, in the manner of a kiwi. The spine attached to the rear of the head rather than the base indicating the horizontal position. This would have allowed them to graze on low-level vegetation, while being able to lift their heads and browse trees when necessary. This has resulted in a down sizing of the height of larger moa.

Although there is no surviving record of what sounds moa made, some idea of their calls can be gained from fossil evidence. The trachea of moa were supported by many small rings of bone known as tracheal rings. Excavation of these rings from articulated skeletons has shown that at least two moa genera (Euryapteryx and Emeus) exhibited tracheal elongation, that is, their trachea were up to 1 metre (3 ft) long and formed a large loop within the body cavity. These are the only ratites known to exhibit this feature, which is also present in several other bird groups including swans, cranes and guinea fowl. The feature is associated with deep, resonant vocalisations that can travel long distances.

Evolutionary relationships

Research published in 2010 has found that the moa’s closest cousins are small terrestrial South American birds called the tinamous which are able to fly. Previously, the kiwi, the Australian Emu, and Cassowary were thought to be the closest ancestors.

Although dozens of species were described in the late 19th century and early 20th century, many were based on partial skeletons and turned out to be synonyms. Currently, eleven species are formally recognised, although recent studies using ancient DNA recovered from bones in museum collections suggest that distinct lineages exist within some of these. One factor that has caused much confusion in moa taxonomy is the intraspecific variation of bone sizes, between glacial and inter-glacial periods as well as sexual dimorphism being evident in several species. Dinornis seems to have had the most pronounced sexual dimorphism, with females being up to 150% as tall and 280% as heavy as males—so much bigger that they were formerly classified as separate species until 2003.

A 2009 study showed that Euryapteryx curtus and Euryapteryx gravis were synonyms. A 2010 study explained size differences among them as sexual dimorphism.

A 2012 morphological study interpreted them as subspecies instead.

Ancient DNA analyses have determined that there were a number of cryptic evolutionary lineages in several moa genera. These may eventually be classified as species or subspecies; Megalapteryx benhami (Archey) which is synonymised with M. didinus (Owen) because the bones of both share all essential characters. Size differences can be explained by a north-south cline combined with temporal variation such that specimens were larger during the Otiran glacial period (the last ice age in New Zealand). Similar temporal size variation is known for the North Island Pachyornis mappini. Some of the other ‘Large’ ranges in variation for moa species can probably be explained by similar geographic and temporal factors.

Classification

2006 species count

It seems likely that continuing research will bring about further changes in classification. The 10 moa species currently recognised are:

- two giant moa – the North Island (Dinornis novaezealandiae) and the South Island (Dinornis robustus)

- three moa with blunt bills and short legs – the eastern (Emeus crassus), the stout-legged (Euryapteryx gravis), and the coastal (Euryapteryx curtus)

- five anomalopterygine moa – little bush moa (Anomalopteryx didiformis), upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus), Mantell’s moa (Pachyornis geranoides), heavy-footed moa (Pachyornis elephantopus) and crested moa (Pachyornis australis).

Habitats and diet

Usually, three or four moa species lived together in a habitat that had particular vegetation types:

- The coastal dunelands of the North Island, with their mosaic of grassland, shrubland and forest, harboured the Euryapteryx assemblage, particularly the coastal moa and Mantell’s moa.

- In the low rainfall zones of the eastern South Island, although the vegetation was slightly different, the Euryapteryx gravis or stout-legged moa was dominant. There were also heavy-footed moa.

- Where there were swamp forests (none now survive), the eastern moa was most common.

- Closed canopy forests were occupied by the little bush moa, with a few Mantell’s moa.

- Mountainous and subalpine zones up to 2,000 metres in the South Island were the stronghold of the upland moa, along with the crested moa.

Giant moa of the Dinornis genus were present in all habitats, from sea level to the subalpine zone, but generally were less common than smaller moa.

Although feeding moa were never observed by scientists, their diet has been deduced from fossilised contents of their gizzards, as well as indirectly through morphological analysis of skull and beak, and stable isotope analysis of their bones. Moa fed on a range of plant species and plant parts, including fibrous twigs and leaves taken from low trees and shrubs. The beak of Pachyornis elephantopus was analogous to a pair of secateurs, and was able to clip the fibrous leaves of New Zealand flax and twigs up to at least 8 mm in diameter. Like many other birds, moa swallowed gizzard stones, which were retained in their muscular gizzards, providing a grinding action that allowed them to eat coarse plant material. These stones were commonly smooth, rounded quartz pebbles, but stones over 110 millimetres (4 in) in length have been found amongst preserved moa gizzard contents. Dinornis gizzards could often contain several kilograms of stones.

Size

Moa were large. Female giant moa (Dinornis genus) were probably over 2 metres tall and heavier than 250 kilograms – significantly more than ostriches or emus. Two extinct birds, the elephant bird (Aepyornis maximus) of Madagascar and ‘the giant duck of doom’ (Dromornis stirtoni) of Miocene Australia, were as tall but bulkier and heavier. Some individuals of Mantell’s moa (Pachyornis geranoides) and the coastal moa (Euryapteryx curtus) from the Far North of the North Island were smaller than a large turkey – less than half a metre tall and weighing under 20 kilograms.

Wingless

Flightless moa were the only birds in the world to lack any vestige of a wing. They had a small bone called the scapulocoracoid, formed from the fused scapula and coracoid. The junction of these two bones is where the humerus of the wing would have been at an earlier stage in evolution.

Feathers

Moa had rough, furry feathers like a kiwi. The feathers lacked the barbules that usually link the filaments. Little is known about the colour, as feathers have been found only for upland moa. These are dark at the base, lightening to greyish-white at the tip.

Feet

Moa had three front-facing toes on each foot, and a small rear toe, often just a spur on the leg. This differs from all other large ratites, who lack a rear toe, and from ostriches, who have just two toes. The moa foot is also distinctive because the tarsus (the scaly part of the leg to which the toes are attached) was very short. In the heavy-footed moa, the breast feathers were barely off the ground.

Head and bill

Moa had small skulls. This is a trait of all ratites, but a 250-kilogram bird would have looked particularly odd with a skull just 23 centimetres long and 12.5 centimetres wide. Their skulls reveal relatively poor eyesight , a good sense of smell (enlarged olfactory region), and a very short bill. The bills of different species vary from robust, sharp and pointed to snip branches and flax, to weaker, rounded ones more suited to plucking soft leaves and fruit.

Reproduction

Fragments of moa eggshell are often encountered in archaeological sites and sand dunes around the NZ coast. Thirty six whole moa eggs exist in museum collections and vary greatly in size (from 120–240 millimetres (4.7–9.4 in) in length and 91–178 millimetres (3.6–7.0 in) wide). The outer surface of moa eggshell is characterised by small slit-shaped pores. The eggs of most moa species were white, although those of the upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus) were blue-green. A 2010 study by Huynen et al. has found that the eggs of certain species were fragile, only around a millimeter in thickness: “Unexpectedly, several thin-shelled eggs were also shown to belong to the heaviest moa of the genera Dinornis, Euryapteryx, and Emeus, making these, to our knowledge, the most fragile of all avian eggs measured to date. Moreover, sex-specific DNA recovered from the outer surfaces of eggshells belonging to species of Dinornis and Euryapteryx suggest that these very thin eggs were likely to have been incubated by the lighter males. The thin nature of the eggshells of these larger species of moa, even if incubated by the male, suggests that egg breakage in these species would have been common if the typical contact method of avian egg incubation was used.” Despite the bird’s extinction, the high yield of DNA available from recovered fossilized eggs has allowed the moa to have its genome sequenced.

Surviving remains

Joel Polack, a trader who lived on the East Coast of the North Island from 1834 to 1837, recorded in 1838 that he had been shown “several large fossil ossifications” found near Mt Hikurangi. He was certain that these were the bones of a species of emu or ostrich, noting that “the Natives add that in times long past they received the traditions that very large birds had existed, but the scarcity of animal food, as well as the easy method of entrapping them, has caused their extermination”.

Owen puzzled over the fragment for almost four years. He established it was part of the femur of a big animal, but it was uncharacteristically light and honeycombed. Owen announced to a skeptical scientific community and the world that it was from a giant extinct bird like an ostrich, and named it Dinornis. His deduction was ridiculed in some quarters, but was proved correct with the subsequent discoveries of considerable quantities of moa bones throughout the country, sufficient to reconstruct skeletons of the birds.

In July 2004, the Natural History Museum in London placed on display the moa bone fragment Owen had first examined, to celebrate 200 years since his birth, and in memory of Owen as founder of the museum.

Bones are commonly found in caves or ‘’tomo’’ (the Maori word for doline or sinkhole; often used to refer to pitfalls or vertical cave shafts). The two main ways that the moa bones were deposited in such sites were: 1. birds that entered the cave to nest or escape bad weather, and subsequently died in the cave; and 2. birds that fell into a vertical shaft and were unable to escape. Moa bones (and the bones of other extinct birds) have been found in caves throughout New Zealand, especially in the limestone areas of northwest Nelson, Karamea, Waitomo and Te Anau.

Densely intermingled moa bones have been encountered in swamps throughout New Zealand. The most well-known example is at Pyramid Valley in north Canterbury, where bones from at least 183 individual moa have been excavated. Many explanations have been proposed to account for how these deposits formed, ranging from poisonous spring waters to floods and wildfires. However the currently accepted explanation is that the bones accumulated at a slow rate over thousands of years, from birds that had entered the swamps to feed and became trapped in the soft sediment.

Feathers and soft tissues

Several remarkable examples of moa remains have been found which exhibit soft tissues (muscle, skin. feathers), that were preserved through desiccation when the bird died in a naturally dry site (for example, a cave with a constant dry breeze blowing through it). Most of these specimens have been found in the semi-arid Central Otago region, the driest part of New Zealand. These include:

- Dried muscle on bones of a female Dinornis robustus found at Tiger Hill in the Manuherikia River Valley by gold miners in 1864

- Several bones of Emeus crassus with muscle attached, and a row of neck vertebrae with muscle, skin and feathers collected from Earnscleugh Cave near the town of Alexandra in 1870 (currently held by Otago Museum)

- An articulated foot of a male Dinornis giganteus with skin and foot pads preserved, found in a crevice on the Knobby Range in 1874 (currently held by Otago Museum)

- The type specimen of Megalapteryx didinus found near Queenstown in 1878 (currently held by Natural History Museum, London.

- The lower leg of Pachyornis elephantopus, with skin and muscle, from the Hector Range in 188 (currently held by the Zoology Department, Cambridge University)

- The complete feathered leg of a Megalapteryx didinus from Old Man Range in 1894 (Currently held by Otago Museum)

- The head of a Megalapteryx didinus found near Cromwell sometime prior to 1949 (currently held by the Museum of New Zealand).

Two specimens are known from outside the Central Otago region:

- A complete foot of Megalapteryx didinus found in a cave on Mount Owen near Nelson in 1980s(currently held by the Museum of New Zealand)

- A skeleton of Anomalopteryx didiformis with muscle, skin and feather bases collected from a cave near Te Anau in 1980.

In addition to these specimens, loose moa feathers have been collected from caves and rockshelters in the southern South Island, and based on these remains, some idea of the moa plumage has been achieved. The preserved leg of Megalapteryx didinus from the Old Man Range reveals that this species was feathered right down to the foot. This is likely to have been an adaptation to living in high altitude, snowy environments, and is also seen in the Darwins Rhea, which lives in a similar seasonally snowy habitat.Moa feathers are up to 23 centimetres (9 in) long, and a range of colours have been reported, including reddish-brown, white, yellowish and purplish. Dark feathers with white or creamy tips have also been found, and indicate that some moa species may have had plumage with a speckled appearance.

Claims of moa survival

The moa is thought to be extinct, but there has been occasional speculation – since at least the late 19th century, and as recently as 1993 and 2008 – that some moa may still exist, particularly in the rugged wilderness of South Westland and Fiordland.

Cryptozoologists and others reputedly continue to search for them, but their claims and supporting evidence have earned little attention from mainstream experts, and are widely considered pseudoscientific.

The rediscovery of the takahe in 1948 after none had been seen since 1898 showed that rare birds may exist undiscovered for a long time.

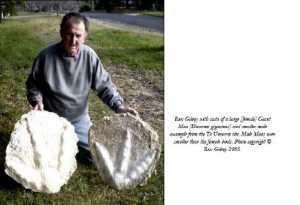

Rex & Heather Gilroy 2008 New Zealand Moa Research

After 20 years of field researches, during our 2000 expedition on Friday 17th march their efforts were finally rewarded. They had begun a search in the Te Urewera National Park inland from Hawkes’ Bay on the eastern side of North Island. Finding an old disused track they followed this up a forest-covered mountainside. Below them, down a steep forest-covered slope was a gully. The track at this point was about 2m wide with a 1.5m bank above, beyond which lay more dense forest covering a lengthy terrace. It was here that they found the indistinct impressions of large bird footprints, which appeared to emerge from the gully, cross the track and scramble up the bank into the forest beyond. Climbing the bank Roy soon found further indistinct large, three-toed footprints in the forest floor.

This link opens a complete account of Rex and Heather Gilroy’s March/April 2008 North Island investigation for evidence of living Moa, principally the Small Scrub Moa, Anomalopteryx didyformis. We were, however, to make perhaps an even more startling discovery, adding a second Moa species to the list of living ‘extinct’ New Zealand ratites.

Another field expedition to New Zealand is planned, hopefully in 2009, during which sites in the South Island will also be investigated. The official scientific view is that the Moas, which were anywhere between 3-4 metres down to 90cm in height, have been extinct for at least the last 600 years.

Having tramped the rugged, often vast and inaccessible mountainous and coastal forestlands of these islands on frequent expeditions since 1980, they have never been able to accept this proposition.

New Zealand radio Interview with Rex on the Moa

The below Link is a 17 min interview with Rex Gilroy, mainly on the Moa in New Zealand and their research.

Self-taught naturalist seeking proof that extinct animals like the Moa and Tasmanian Tiger are still around. (duration: 17′44″)

http://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/ninetonoon/20080125>

Rex Gilroy’s fascinating and exhaustive website on his research and expeditions. http://www.mysteriousaustralia.com/

A new documentary in the making from the team at Wildnewzealand Films. The movie sets out to prove that the Moa is not an extinct bird in New Zealand.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wz1Ob06liRQ

NZ Maori: Moa Hunters – the Story of the Wairau Bar Marlborough New Zealand

700 year old Early Maori Settlement. Prof Kenneth Cumberland looks at New Zealands Giant Moa Bird and its demise and the Hunters Malcom Hall, Julius Von Haast and the British Natural History Museum, London

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySVafRszq_E

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cbK0wdlxcMo

Monsters we met: New Zealand Giant Moa

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JF_hWMXPI5o

Rex and Heather Gilroy’s – New Zealand Moa Expedtion 2008 – Complete account

http://www.mysteriousaustralia.com/newsletters/2008newsletter/2008_may_monthly_newsletter.html

Articles – www.teara.govt.nz

Terra nature – http://terranature.org/moa.htm

A New Zealand Herald article dated Sunday Dec 22, 2013

Giant moa wasn’t so robust

A new study has found its bones were more slender than first believed, which has resulted in a recalculation of the birds’ size.

Instead of studying just the birds’ leg bones to determine its weight, the study scanned the entire skeleton, which revealed slimmer bones that meant its weight could be more accurately estimated.

The study was led by Manchester biomechanics student Charlotte Brassey, in collaboration with palaeobiologist Professor Richard Holdaway of Canterbury University’s School of Biological Sciences.

Professor Holdaway said earlier estimates of the birds’ weight had the moa weighing up to 300kg. This study points towards a weight of about 200kg.

The legs of the moa, or the dinornis robustus (literally meaning robust strange bird), were similar to its distant relatives such as the ostrich, emu and rhea, Professor Holdaway said.

Ms Brassey said they already knew moa had disproportionately wide leg bones, yet previous estimates of their body mass had been based on only those bones, which probably resulted in overestimates.

After scanning the whole skeleton the new estimates were considerably lower.

The largest moa still weighed in at a hefty 200kg, or 30 family-sized Christmas turkeys, and if revellers wanted to roast one for Christmas dinner, they would have to start cooking it tomorrow, Ms Brassey said. – APNZ

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11176750

A Haunted Auckland Cryptozoological Expedition in the Urewera National Park to search for evidence of a Moehau or Small Moa population, present or past is planned for early 2014.