In 1986 in the basement of the Marseille Museum of Natural History a primitive type specimen of a large gecko was found stuffed, unlabeled, lacking any record of its collection date or its point of origin and judging from the specimen must have been there for over a century.

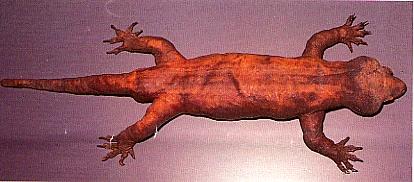

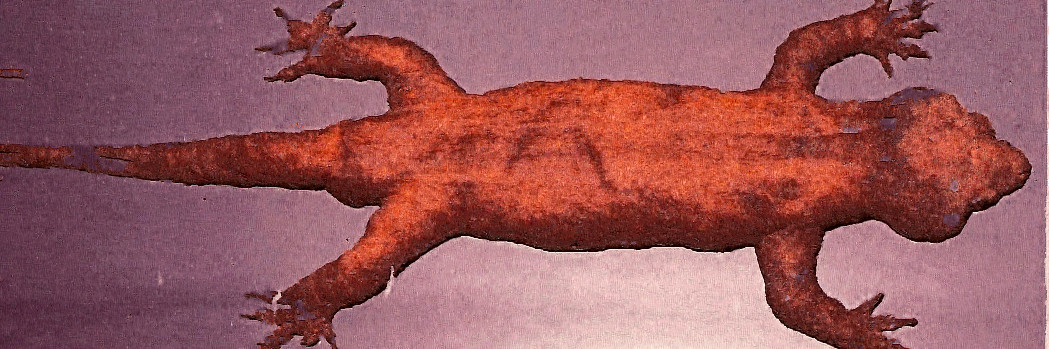

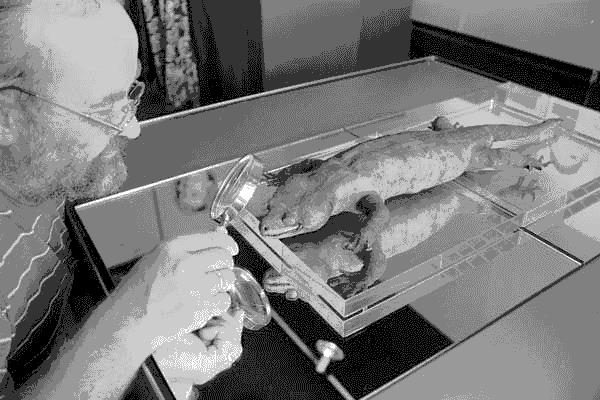

Once examination of this specimen was performed it was found to be a species unknown to science. The type specimen consisted of a single skin and partial skeleton, the skin was stuffed and mounted on a wooden plank. It measured 370mm from snout to vent and had a total length of 622mm. This meant this unique specimen of gecko was 54% larger than the largest living Gecko, The New Caledonian Giant Forest Gecko -Rhacodactylus leachianus.

Closer examination showed this gecko was similar to the Brown Forest Geckos – Hopolodactylus spp. of New Zealand ( Bauer 1986).

This seemed strange as no geckos that big were present in New Zealand and the only thing close to that size was the Kawekaweau of Maori folklore.

Could this actually be a representative of that mythical animal that had supposedly not been seen for over 100 years?

The Maori said the Kawekaweau represented the souls of dead ancestors of anyone who saw it and sighting one was an omen it was that person’s time to join them. Thus they were largely avoided and left alone by the Maori.

It was described as being about 2 feet long and as thick as a man’s wrist. They were said to be have a brown basal colouration with a red, or sometimes green, striped pattern.

It was found in the Totara – Agathis australis and Kauri – Metrosideros robusta forests. It was found under the bark of these trees, typical gecko behaviour and believed to be semi-arboreal.

Other reports indicated that it inhabited caves and rock piles and was said to be arboreal and semi-aquatic. The large eyes of the type specimen and bark hiding characteristic seem to indicate a nocturnal species.

It was supposed to have fed on fruit, nectar, large insects and small invertebrates, including other lizards and no doubt not excluding its own young.

From the size of this lizard it may also be assumed that it may have included birds eggs in its diet as with New Zealand’s ample avian fauna they would not have been in short supply and would have been a viable food source for this species. This animal would have been an important predator in its ecosystem.

This Gecko seems to have been prevalent in the North Island, osteological evidence seems to suggest that H. delcourti or a similar large gecko may have been once prevalent in the Otago region of the South Island as well.

Bones discovered in the Eamscleugh Cave in Central Otago were found in association with rat bones which indicated they were of quite recent origin.(Hutton 1875).

Captain Cook was the first one to record Maori tales of giant lizards in New Zealand in 1777, including tales of the Kawekaweau. Later European descriptions make vague mention of a pair of these lizards that were captured and kept. Regrettably one was eaten by a cat and the other escaped and was not sighted again.

The last known specimen seen alive was caught by a Maori chief of the Urewera Tribe in 1870, while hiding underneath some bark. In that same year a dead large Gecko was washed down the Waima creek, from the Waoku Plateau area.

In 1986 when the discovery of the type specimen was made, rumour abounded of a population of these lizards near Rotorua, this rumour was however, never substantiated. In April 1990 several sightings of a large gecko were reported in the daily press in New Zealand.

Most of these recent sightings were centred around the Gisborne, the Waipoua Forest and Waoku Plateau. Some of these sightings were investigated by local Herpetologists and though many were dismissed as misidentifications a few could no be explained as easily. It would be quite easy for a large species of Gecko to still exist in some of the isolated areas of the country as new species are still being discovered.

Two smaller new species of Hopolodactylus were discovered as recently as 1981 and 1984, so there is hope that the larger delcourti may turn up. Finding it however, will be no easy task as its nocturnal habits, possible small population density, isolated locations and the fact that it hides during the day will make it very hard to find.

After its discovery the origin of the lizard remained a mystery for quite a while, some speculated the type specimen may have originated from the French Island Territory of New Caledonia, this would explain it being in a French Museum, if this were true it would mean re-evaluating the distribution of the Hopolodactylus genus.

The evidence for this was based on the fact that no other New Zealand lizards were at the Museum, most of the specimens at the Museum originated from the Pacific Islands. Regrettably no documentation existed for any specimens donated to the Museum between 1833 and 1869. It can therefore be assumed that the type specimen may have entered the Museum during this period.

If any of these animals still exist that are at very high risk. Habitat destruction, predation by cats, weasels and stoats and low breeding densities could cause this species, if it still exists, to join those species already extinct and only known from a single type specimen.