In Māori mythology, taniwha (Māori pronunciation: [Tanifa] are beings that live in deep pools in rivers, dark caves, or in the sea, especially in places with dangerous currents or deceptive breakers (giant waves). They may be considered highly respected kaitiaki (protective guardians) of people and places, or in some traditions as dangerous, predatory beings, which for example would kidnap women to have as wives.

Linguists have reconstructed the word taniwha to Proto-Oceanic tanifa, with the meaning “shark species”. In Tongan and Niuean, tenifa refers to a large dangerous shark, as does the Samoan tanifa; the Tokelauan tanifa is a sea-monster that eats people. In most other Polynesian languages, the cognate words refer to sharks or simply fish. Anthropologists such as A. Asbjørn Jøn have recognised that the taniwha has “analogues that appear within other Polynesian cosmologies”.

Linguists have reconstructed the word taniwha to Proto-Oceanic tanifa, with the meaning “shark species”. In Tongan and Niuean, tenifa refers to a large dangerous shark, as does the Samoan tanifa; the Tokelauan tanifa is a sea-monster that eats people. In most other Polynesian languages, the cognate words refer to sharks or simply fish. Anthropologists such as A. Asbjørn Jøn have recognised that the taniwha has “analogues that appear within other Polynesian cosmologies”.

At sea, a taniwha often appears as a whale or as quite a large shark; compare the Māori name for the Great White Shark : mangō-taniwha. In inland waters, they may still be of whale-like dimensions, but look more like a gecko or a tuatara, having a row of spines along the back. Other taniwha appear as a floating log, which behaves in a disconcerting way.

Some can tunnel through the earth, uprooting trees in the process. Legends credit certain taniwha with creating harbours by carving out a channel to the ocean. Wellington’s harbour, Te Whanganui-a-Tara, was reputedly carved out by two taniwha. The petrified remains of one of them turned into a hill overlooking the city. Other taniwha allegedly caused landslides beside lakes or rivers.

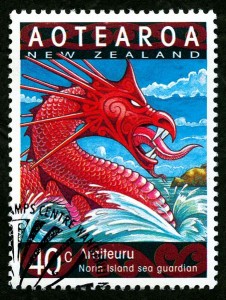

Many taniwha were associated with the sea. A large number were said to have come with the voyaging canoes that brought the Polynesian ancestors of the Māori people to Aotearoa (New Zealand). Most taniwha have associations with tribal groups; each group may have a taniwha of its own. The taniwha Ureia, depicted on this page, was associated as a guardian with the Māori people of the Hauraki district. Many well-known taniwha arrived from Hawaiki, often as guardians of a particular ancestral canoe. Once arrived in New Zealand, they took on a protective role over the descendants of the crew of the canoe they had accompanied. The origins of many other taniwha are unknown.

When accorded appropriate respect, taniwha usually acted well towards their people. Taniwha acted as guardians by warning of the approach of enemies, communicating the information via a priest who was a medium; sometimes the taniwha saved people from drowning. Because they lived in dangerous or dark and gloomy places, the people were careful to placate the taniwha with appropriate offerings if they needed to be in the vicinity or to pass by its lair. These offerings were often of a green twig, accompanied by a fitting incantation. In harvest time, the first kumara or the first taro was often presented to the taniwha.

Arising from the role of taniwha as tribal guardians, the word can also refer in a complimentary way to chiefs. The famous saying of the Tainui people of the Waikato district plays on this double meaning: Waikato taniwha rau (Waikato of a thousand chiefs)

In their role as guardians, taniwha were vigilant to ensure that the people respected the restrictions imposed by tapu. They made certain that any violations of tapu were punished. Taniwha were especially dangerous to people from other tribes. There are many legends of battles with taniwha, both on land and at sea. Often these conflicts took place soon after the settlement of New Zealand, generally after a taniwha had attacked and eaten a person from a tribe that it had no connection with. Always, the humans manage to outwit and defeat the taniwha. Many of these taniwha are described as beings of lizard-like form, and the some of the stories say the huge beasts were cut up and eaten by the slayers. When Hotu-puku, a taniwha of the Rotorua district, was killed, his stomach was cut open to reveal a number of bodies of men, women, and children, whole and still undigested, as well as various body parts. The taniwha had swallowed all that his victims had been carrying, and his stomach also contained weapons of various kinds, darts, greenstone ornaments, shark’s teeth, flax clothing, and an assortment of fur and feather cloaks of the highest quality.

In their role as guardians, taniwha were vigilant to ensure that the people respected the restrictions imposed by tapu. They made certain that any violations of tapu were punished. Taniwha were especially dangerous to people from other tribes. There are many legends of battles with taniwha, both on land and at sea. Often these conflicts took place soon after the settlement of New Zealand, generally after a taniwha had attacked and eaten a person from a tribe that it had no connection with. Always, the humans manage to outwit and defeat the taniwha. Many of these taniwha are described as beings of lizard-like form, and the some of the stories say the huge beasts were cut up and eaten by the slayers. When Hotu-puku, a taniwha of the Rotorua district, was killed, his stomach was cut open to reveal a number of bodies of men, women, and children, whole and still undigested, as well as various body parts. The taniwha had swallowed all that his victims had been carrying, and his stomach also contained weapons of various kinds, darts, greenstone ornaments, shark’s teeth, flax clothing, and an assortment of fur and feather cloaks of the highest quality.

Many taniwha were killers but in this particular instance the taniwha Kaiwhare was eventually tamed by Tamure. Tamure lived at Hauraki and was understood to have a magical mere/pounamu with powers to defeat taniwha. The Manukau people then called for Tamure to help kill the taniwha. Tamure and Kaiwhare wrestled and Tamure clubbed the taniwha over the head. Although he was unable to kill it, his actions tamed the taniwha. Kaiwhare still lives in the waters but now lives on kōura (crayfish) and wheke (octopus).

Modern controversy

Beliefs in the existence of taniwha have a potential for controversy where they have been used to block or modify development and infrastructure schemes.

In 2002, Ngāti Naho, a Māori tribe from the Meremere district, successfully ensured that part of the country’s major highway, State Highway 1, be rerouted in order to protect the abode of their legendary protector. This taniwha was said to have the appearance of large white eel, and Ngāti Naho argued that it must not be removed but rather move on of its own accord; to remove the taniwha would be to invite trouble. Television New Zealand reported in November 2002 that Transit New Zealand had negotiated a deal with Ngāti Naho under which “concessions have been put in place to ensure that the taniwha are respected”.

In 2001 “another notable instance of taniwha featuring heavily within the public eye was that of a proposed Northland prison site at Ngawha which was eventually granted approval through the courts.” Māori academic Dr Ranganui Walker, in a detailed letter to the Waikato Times, said that in the modern age a taniwha was the manifestation of a coping mechanism for some Māori. It did not mean there actually was a creature lurking in the water, it was just their way of indicating they were troubled by some incident or event.

Pingback: The Taniwha | Paranormal NZ | Mysterious Times

We are not troubled, we just do not belong in colonised civilisations. Nature is home, cities are killers. James Crook poisoned our once beautiful flourishing lands.

True history will reveal itself when the time is ready.